The Himalayas are still home to thousands of manuscripts that remain actively cared for by their communities. The region has faced incredible challenges over the last millennia and yet the temples, murals, statues, and texts that have weathered the centuries continue to play an important role in the living culture of tens of thousands of Tibetan Buddhists in Ladakh, Himachal, and Nepal, and beyond. One organization that has done significant preservation work in the region is the Tibetan Manuscripts Project at the University of Vienna. When BDRC conceived of the Buddhist Digital Archives as a web of Buddhist resources, TMPV was the first resource that we reached out to, and the first to join the BUDA-field! For their preservation work, they have traversed the length of the western Himalayas from Alchi to Zanskar.

In the 1990s when Professor Helmut Tauscher started taking photographs of Buddhist manuscripts in Spiti, he couldn't have imagined that thirty-one years later his photos would allow people all over the world to read these precious texts. As part of the University of Vienna-Tibetan Manuscripts Project and the Resources for Kanjur and Tanjur Studies project, Helmut Tauscher, Bruno Lainé and Markus Viehbeck have documented, and made accessible, valuable manuscripts from the western and southern Himalayas, including rare editions of the Kangyur and Tengyur. They have made an immense contribution to the study of Tibetan Buddhism.

Phugthar Monastery, Zanskar. Photo courtesy of Bruno Lainé.

Phugthar Monastery, Zanskar. Photo courtesy of Bruno Lainé.We spoke to Bruno Lainé, who has been with the project since the late 1990s when Helmut Tausher hired him to order the photographical material made from Tabo and Gondhola. Bruno ended up creating a digital Kangyur catalog from scratch. There were more difficult challenges in store. On his trips with Helmut in the field in Ladakh, Zanskar, Kinnaur or Spiti in search of Tibetan manuscripts, they faced landslides, floods, and even a detention. When they were in Charang in the Kinnaur region, there was a dispute between the villagers over the ownership of and authorization of photographing certain manuscripts, and Helmut and Bruno were held for a few days by the villagers, and treated very well, Bruno pointed out.

Helmut and Bruno were looking for complete collections of the Kangyur and also for manuscripts of what Helmut called the proto-Kangyur—collections that were compiled before the Kangyur was canonized in the 14th century in Tibet. Their finds were worth the challenges. They found Kangyurs at Hemis and Shey palaces in Ladakh and canonical collections in Zanskar. The Gondhola collection, discovered by Deborah Klimburg-Salter and Christian Luczanits, is an early 14th century manuscript collection comprising 397 texts in 36 volumes. Handwritten in Uchen script, it seems at least parts of this collection were written for the local rulers of Gondhola, to whose descendants the Kangyur belongs. The TMPV team is now active in the Nepalese regions of Mustang and Dolpo and have already discovered several collections of great importance as in the monasteries of Namgyal and Lang.

Most of these wonderful manuscripts are available on the Buddhist Digital Archives for scholars and practitioners thanks to the dedicated efforts of Helmut Tauscher, Bruno Lainé, and Markus Viehbeck, and of course the University of Vienna.

Bruno Lainé was kind enough to do a short Q&A with us.

Bruno & Géza Bethlenfalvy with Tsewang Phuntsog. Photo courtesy of Bruno Lainé.

Bruno & Géza Bethlenfalvy with Tsewang Phuntsog. Photo courtesy of Bruno Lainé.Q&A with Bruno Laine

Why are you interested in preservation?

I am interested in preservation, but above all in dissemination. It is important to preserve the cultural heritage in good conditions, but if this is only to lock it in a safe where no one can consult it, it is of no use. This is why the Vienna project takes as many images as possible and then makes them available to the academic community as well as to the interested public. BUDA is the perfect platform for us to put our images online and access the other canonical collections available.

How has new technology changed what we can do with texts?

I remember before the arrival of new technology. At the time, there were no digital resources to help us. Canonical studies were limited to the witnesses one had at his disposal (usually 5 Kanjurs) and to search for a quotation sometimes took days. So you can imagine how laborious it was to identify the texts and the quotation. At this point, I started to create a database with the entries of the then available catalogs, so that it was easier for us to find cross references. From this time onwards, I also accompanied Helmut Tauscher in the field and we were mainly in Ladakh proper. We at first were only interested in "old" manuscripts (up to 15th cent.), but we decided to integrate "newer" canonical manuscripts to our studies since they contain a lot of information on the formation of the Tibetan Canon and we started to photograph complete Kanjurs and other canonical collections. Now, with one click you can display a large number of Kanjurs, view the images, and for some even do full-text search.

What are the achievements of the Tibetan Manuscripts of Vienna project?

Concerning TMPV, a big achievement was to make canonical studies more complex. The number of available collections has increased considerably and TMPV has shown that the Tibetan canon is not confined to two groups (Tshal pa & Them spangs ma) with a few isolated independent Kanjurs, but that the relations between Kanjurs are much more complicated than we had believed. Tibetans have been very active in this area. Resources of Kanjur and Tanjur Studies offers tools that allow easy navigation in this canonical literature. It also participated in the (r)evolution from paper Kanjur to digital Kanjur. I hope that with TMVP, we can continue to chase new collections and make them available. For rKTs I hope we will offer an even better and more precise navigation system.

What does the Buddhist Digital Archives (BUDA) mean for you?

The Vienna project is a very small structure and we don't have the capacity to do everything ourselves. Collaborating with BDRC allows us to increase our capabilities, especially concerning images. BDRC takes care of image management and rKTs provides catalogs and data for canonical texts. It would be silly to have two institutions working on the same things at the same time without any exchange between them. It is also a mutual motivation; by exchanging with other people, we get a different and broader view of the topic we are dealing with.

Open Data means that we can aggregate an ever greater amount of data to improve our navigation system. It means above all that by sharing our data between us, we do not need to do what others have already done. You can focus on your work, share your results with others, and in turn benefit from those of others.

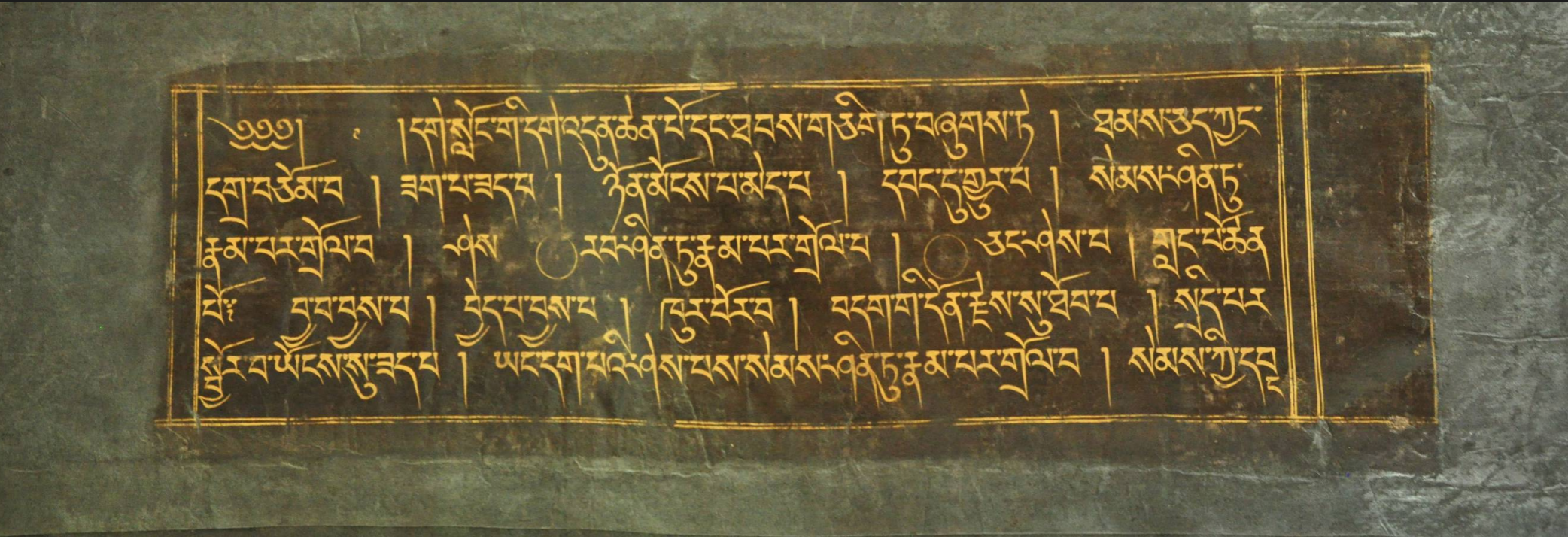

An incomplete version of the handwritten Golden Kangyur of Hemis Palace, from the 17th century. BDRC Resource ID: W4CZ45315.

An incomplete version of the handwritten Golden Kangyur of Hemis Palace, from the 17th century. BDRC Resource ID: W4CZ45315.Interested users can find all of the University of Vienna-Tibetan Manuscripts Project texts freely available here in the Buddhist Digital Archives. We are grateful to the TMPV for their heroic work and to the families of the Western Himalayas who have preserved and shared their priceless heritage texts.

Pingback:BDRC is Using Artificial Intelligence to Generate Wisdom, Part 2: Training AI to Crop Manuscripts - Buddhist Digital Resource Center

Posted at 21:07h, 01 June[…] like those taken by the Tibetan Manuscripts Project Vienna (TMPV) on field trips in India (see our article on TMPV here and browse their collection in our archive), resulting in images containing 2 page […]