"I throw my glass so that others would throw their jade."

—Peter Gruber quoting a Chinese proverb

Long-time friends of BDRC will know of Peter Gruber: founder of the Gruber Foundation Science Prizes, friend of our founder Gene Smith, and a major benefactor of Buddhism in America who played an important role in bringing Buddhist teachings to the West. He was also a financial genius, a pioneer of emerging markets who managed money for Sir John Templeton and George Soros, among others. Less well known is the origin story of Peter's engagement with Buddhism, which was to prove a life-long passion, a religion and a philosophy. Recently BDRC reviewed some of Peter Gruber's papers, which shine a light on the early years of his interest in Buddhism.

Peter was born in Hungary in 1929 to an established family in Budapest's Jewish community. Ten years later, the rise of Nazi Germany and World War II forced the family into exile, to India. During the Japanese bombing of Calcutta, his parents sent Peter and his brother away, for their safety, into the Himalayan foothills where they studied with Jesuit brothers at St. Joseph's School in Darjeeling. Originally known as Dorje Ling, the land of the thunderbolt, and part of the Tibetan empire, Darjeeling was a trading post for Tibetan traders who came on horses and mules. Darjeeling and neighboring Kalimpong, called the Constantinople of the East, were at the crossroads of British India, Nepal and Tibet. As such they were both a pit stop and destination for Tibetan traders as well as Tibetan lamas. Peter's formative years in Darjeeling set the template for the rest of his life—Peter would become both a trader and a Buddhist.

Peter (right) with his brother in Darjeeling during their school days.

After a stint in the Army, Peter started out on Wall Street, learning to trade at a small brokerage firm. But he knew that worldly success was empty without spiritual pursuits. Exposed to both Judaism and Christianity from a young age, it was Buddhism that helped him make sense of his life and understand the trauma and suffering he had already seen. Still in his twenties, he established the Oriental Studies Foundation—to introduce and disseminate Buddhist philosophy, both at home and abroad.

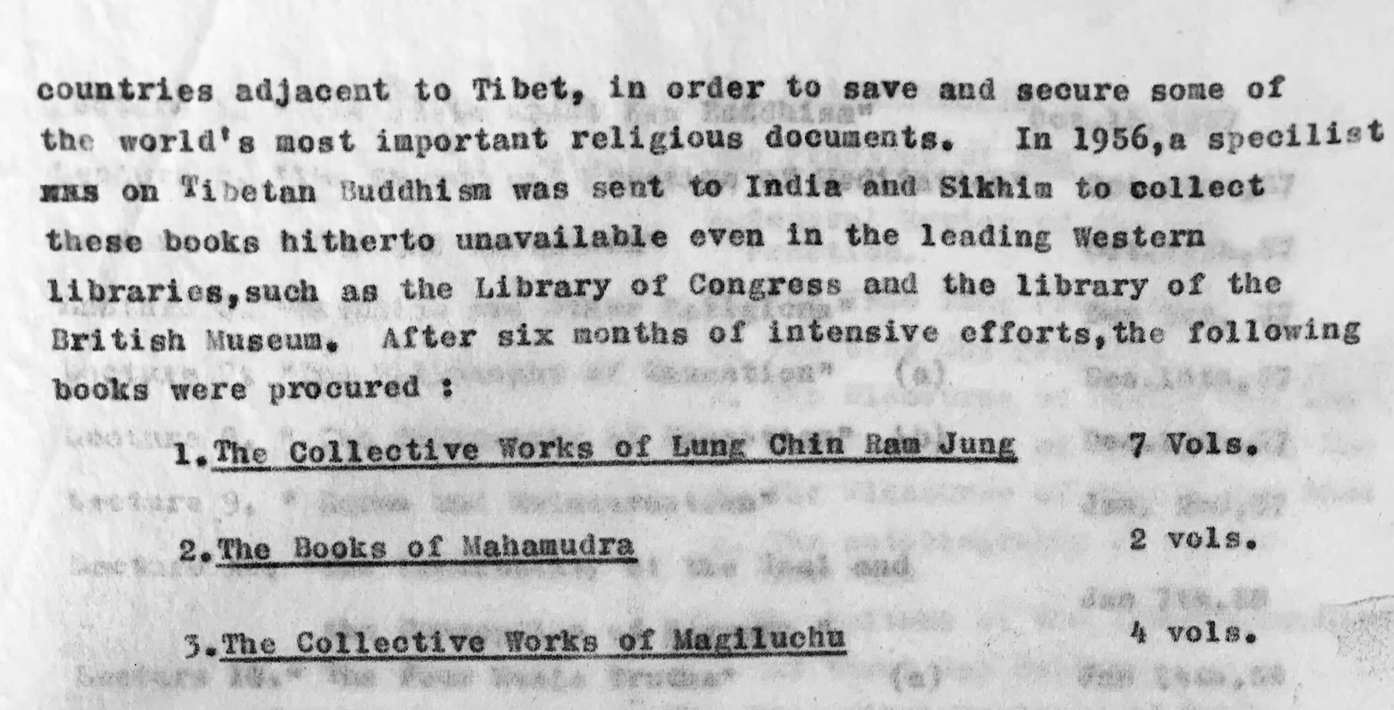

With the Oriental Studies Foundation, Peter sought out and preserved a number of valuable Tibetan Buddhist manuscripts, sponsored the translation of books on Buddhism and produced a series of public lectures on Buddhist philosophy. His contributions were a key step in the preservation of Buddhist texts at a critical period. As one of OSF's reports stated, "…the Oriental Study Foundation, with its limited resources and capacities has undertaken a project for procuring as many Tibetan books and manuscripts as it can from countries adjacent to Tibet, in order to save and secure some of the world's most important religious documents. In 1956, a specilist [sic] on Tibetan Buddhism was sent to India and Sikkim to collect these books hitherto unavailable even in the leading Western Libraries…"

From an Operational Report of the "Oriental Study Foundation," as it was styled then, we can see that in 1956 OSF collected over 30 volumes of invaluable Tibetan Buddhist texts.

Peter's contributions were crucial in bringing the Dharma to the West. In 1961, Peter and the Foundation published Edward Conze's first translations of the Prajnaparamita, the foundational scriptures of Mahayana Buddhism. In 1962, Peter published Garma Chang's English language translation of the Hundred Thousand Songs of Milarepa. These seminal texts introduced Tibetan Buddhism to an English language audience.

The mission of the Oriental Studies Foundation became urgent as Tibetan refugees started pouring into Darjeeling from across the border. As a Jewish refugee, Peter's life was marked by war and exile—it was inevitable that he would deeply empathize with the struggle of Tibetan and Chinese refugees making a new life. We can see in letters that he wrote during this period, to President Kennedy, to the Director of the U.S. Agency for International Development, to the Office of Refugees and Migration Affairs, that he's deeply concerned as he urges the US government to help the refugees. He wrote to President Kennedy on June 5, 1962, "Many of these refugees are Buddhists, who are desperate, and in need of help….Enclosed you will find letters of request for aid that we have received. Your guidance in directing us to the people who may be of help would be greatfully [sic] appreciated."

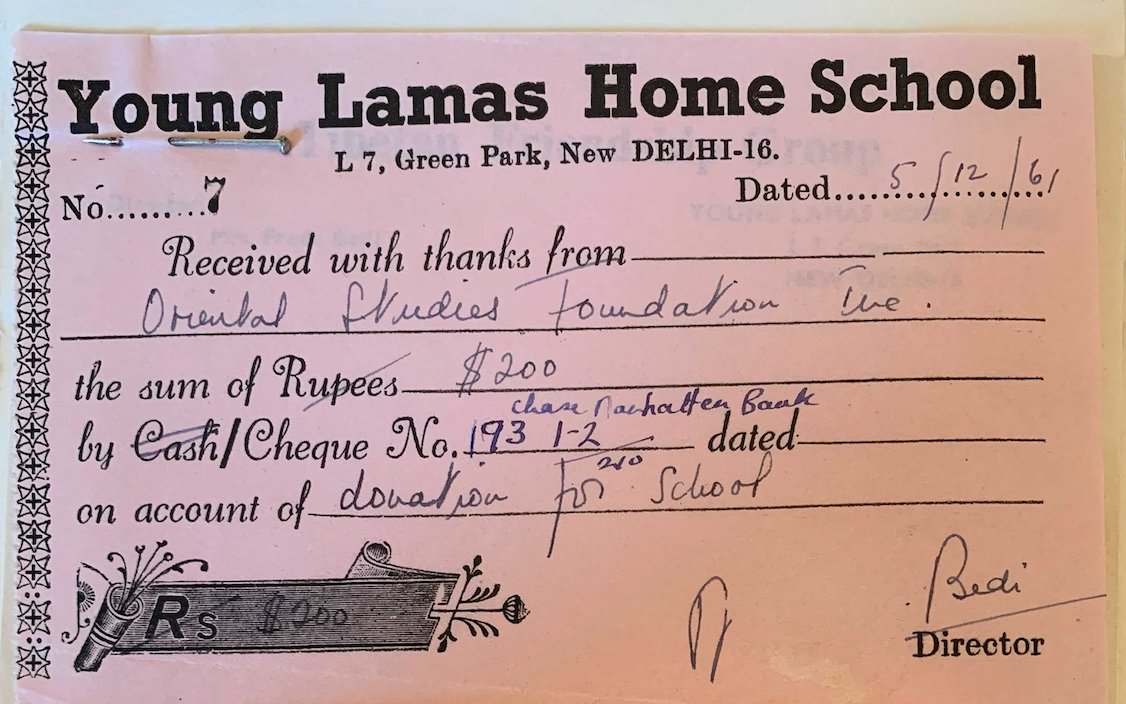

One of the notable acts of philanthropy in his life was a $200 donation made in 1961 to support the newly established Young Lamas Home School. Started by Mrs. Freda Bedi, a Gandhian revolutionary and the first Western woman to ordain as a Tibetan Buddhist nun, this school educated an entire generation of Tibetan teachers including Chogyam Trungpa, Lama Zopa, Akong Rinpoche and Gelek Rimpoche who brought the Dharma to the West. Its effect on the Dharma is incalculable.

Receipt of the $200 donation, signed by Mrs. Bedi herself. The Young Lamas school educated an entire generation of Tibetan teachers who brought the Dharma to the West.

Peter believed in luck and serendipitous connections. In an interview, he spoke about the role of luck and serendipity in his life and said, "I'll tell you one thing. The best thing that happened to my life is Patricia." His wife Patricia Murphy Gruber, a psychotherapist, ran the Peter and Patricia Gruber Foundation, and co-created the prestigious Gruber Prizes in cosmology, neuroscience and genetics, as well as the Gruber Program for Global Justice and Women's Rights at Yale University. For her far-reaching philanthropy, Pat was awarded an honorary PhD from the Weizmann Institute of Science in Israel. Pat served on the board of BDRC for more than ten years and has made major contributions to the vitality and vision of our organization.

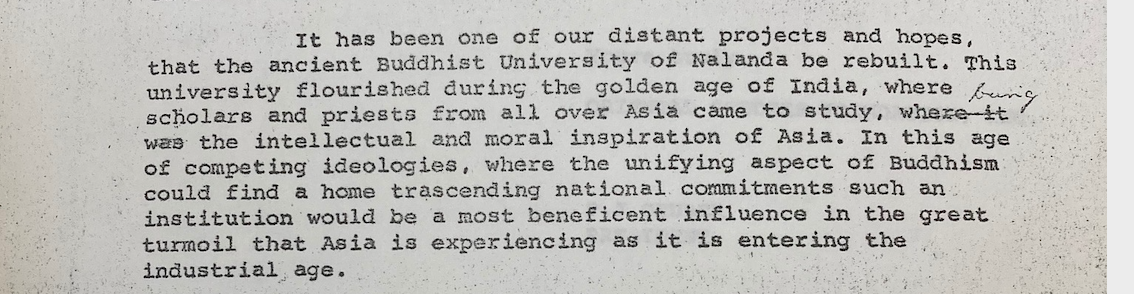

Certainly Peter and Pat's first meeting with Gene, our founder, was a karmic act of serendipity— a Buddhist contractor hired to do some roof work on their home introduced them to Lama Surya Das who brought Gene's work to their notice. Peter and Gene immediately recognized each other as kindred spirits. With the Tibetan Buddhist Resource Center, Gene was doing exactly what Peter had set out to do: to preserve and disseminate the teachings of the Buddha. Years before meeting Gene, Peter had the idea of using PL480 Food for Peace funds for Buddhist literary preservation (as recorded in letters to American officials), which Peter discovered Gene had personally accomplished. They were brothers in the Dharma, and pioneers in their respective fields who shared a mission; their friendship seemed preordained. They spent long hours talking about Buddhist texts, ideas and the practices. Peter and Patricia became preservation partners of our organization; our journey, and our impact, would not be the same without them, and we are incredibly grateful for their foundational support.

Excerpt from Peter's letter to the Director of USAID in 1964, to advocate for the Oriental Studies Foundation and its Buddhist mission.

Peter was a man who achieved remarkable worldly success. But he never faltered in his spiritual progress; he practiced tummo, a highly advanced meditation. Pat said about Peter, "In addition to being a wonderful, warm person and a great partner and the love of my life, living with Peter was a teaching." He always picked up pennies that he found on the street, saying he may not be the smartest guy on the street but he knew an opportunity when he saw one. In fact, he was the smartest guy on the street. Pat remembers that people always came to Peter and asked, what's the secret to the market? Peter's answer was Buddhist to the core: "There really are two secrets: the market goes up and the market goes down."

In its impermanence and its cyclic nature, the market was a lot like samsara. Peter understood impermanence, and as he fell seriously ill, first with shingles and then its resulting complications, he closed his company and assessed his work in the world. Pat took care of him until he passed away at their home in St. Thomas in 2014. The world lost a visionary, a pioneer of the markets who was also a pioneer of Buddhism in America, who left a legacy that continues to benefit all whose lives are brightened by the Dharma.

Sorry, the comment form is closed at this time.